Psychose and Evil

door Margreet de Pater

How personal encounter evaporates evil.

The stigma, the routes.

‘’Oh psychosis, I know someone, she was a daughter of my nephew, she committed a murder.” “a friend of my became psychotic, he was admitted to hospital, A one flew over the cuckoo’s nest like ward, he stayed there for years and years and finally committed suicide.”. These were the comments that I got from members of the enlightened old people organization I recently joined, when I prepared a lecture.

The papers publish articles regularly: A guy in Alphen aan de Rijn shot a whole bunch of people in a mall, a guy murdered a minister, and a young guy committed two murders. He appeared on the ward with blood all over him and the personnel did nothing… His mom had phoned the facility and said that he was acting weird. They just gave him another pill and said to her not to worry…

It does not work trying to tell people that in the 39 year that I have worked as a psychiatrist in a crisis center and an assertive community treatment team and that I have never met a psychotic person who murdered someone. Also that the percentage of psychotic people who kill does not exceed the average of all people, and that they more often are victim of crime than average.

People remember the bad things, that is how the brain works, we are programmed to detect danger. And in this way stigma is formed.

People who have personal experience with someone who was psychotic, family and friends have bad experiences too. They often remember how a psychotic person said all kind of scary things, how formerly nice well behaving persons surpassed many social boundaries, talked about family secrets, offended people. Yes they tried to talk to him or her, tried to convince him or her that the ideas were wrong, that they must use medication. Anger or friendly persuasion had not worked.

How it was in de past.

They phoned psychiatric services who were reluctant to come, because the patient was not motivated to get help. Then finally the police came and he or she was put in a cell, an unknown doctor came and with some luck judges the patient as dangerous. Then he or she was transported to a hospital. Often the family was not admitted because of privacy reasons.

That was at least the common practice when I was a psychiatrist, I hope you that you can tell me there are better solutions now.

And after this happens the ‘’patient’’ is often no longer invited on birthday parties or funerals, emotions of people become a secret. The conversations become about taking medication or not. If a person acts strangely on a bus, everybody becomes absorbed in the newspaper and is relieved when a controller enters and takes action. The psychosis susceptible person lives in a void, the only companions are the voices and the anchor in life the delusions.

But a psychosis can also be a turning point for new, better relationships.

The organisation of care

This why good crisis intervention is so important. This asks a lot of courage from everyone involved, and a good organisation of care, where it is possible that everyone involved meets each other. This includes some continuity of clinicians, so that people don’t need to tell their story over and over again and important information is lost, so that a bond can grow between clinicians, people with psychosis and family.

Sometimes in the organisation of care good things happen. That was in the nineteens when the managers of ‘’RIAGG Stad Utrecht” decided that people who are in trouble have the right to get access to good crisis intervention. This was to prevent a bad course of psychiatric problems. Crisis theory influenced clinicians and managers at that time. The idea was that a crisis could be a change point from bad to good.

People could phone the center 24 hours a day. They could come to the center or a team of crisis therapists could make a house call. They could visit families once a day if this was necessary for 3 months long. I was lucky to work as a psychiatrist then at that place.

So, I had the opportunity to meet, together with my colleagues, fresh, acutely psychotic persons in their family. Yes we had to change our practice somewhat. We didn’t wait any longer for the consent of the psychotic person. We treated the family as the ones who were in need for help. We explained that to the psychotic person who didn’t want to talk with us: “We come for your family, because they are anxious and worried. ‘’ ‘’Yes, help my mom, she needs it’’ answered he or she.

We had the opportunity to work together with the police in a good way. We joined expertise when Interventions in a potential dangerous situation were necessary. We did interventions together. They helped us containing damaging behavior, we helped them to communicate in a not escalating way explaining that a confused person acts through fear and reacts in a different way than a criminal who wants to do bad things.

The crisis intervention

The aim of our intervention was not to cure. We made the observation that defining persons behavior as an illness, and that medication could help, made that the person with psychosis often begun a combat: “No he or she had come to important insights finally, and no one could take that away.”

We didn’t try to cure the family either: ‘’We do not asking for therapy! He/she is the one who is mad!, So come on doctor do something for your salary!”.

The aim of the intervention was to contain the situation.

So we did a family talk and invited everyone, including the psychotic person to tell about his or her experiences. What were his/her feelings, his/her fears, his/her worries?

For the psychotic person it was the first time that he was informed about the feelings of others and the impact of his/her behavior.

We did some explanation of psychotic behavior, not the medical one, but (according to the situation) Jungian or in words that were in our estimation acceptable for the psychotic person.

Then we did some limit setting. Often families preferred to leave that to us, but we explained that we could not do it without closely working together with everyone.

It was all about behavior, not about changing thinking, we were not big brother. So for instance it was not allowed to wake up the mother in the middle of the night talking about the downfall of the world, but to leave that for the next morning and for father not to shout and for mother not talk about what the patient was really thinking.

And yes we gave medication on the first or second visit. We explained that medication helped to make a choice as to how to behave. Sometimes we organized a compulsory admission for a short time, parents explaining the conditions for coming home again.

The outcome

There were less hospitalizations for a shorter time. Family members, who had the opportunity to be a hero, felt more confident and stronger. They had the fear that setting limits would estrange them from their family member. The opposite was true, it often became better. They were less concerned with the opinion of others.

And after that

We had family conversations about all sort of subjects. For instance: father had walks with his son and spoke about his past. There were talks on family stories which had never been .talked about before. The now less psychotic person talked about for the first time about what he or she did not like in the family, sometimes about traumatic events in or outside the family.

In my impression we had the same experiences as open dialogue therapists, I met later.

The final outcome?

So was this crisis intervention a prevention of a bad course? A evaluation was not possible because the intervention was not standardised enough (Talma) I only can give you my impressions: it was a prevention of bad family interactions. After an reorganisation –,there was more continuity of care after crisis intervention– I saw families who had not this kind of intervention, I heard more hateful comments about patients and about clinicians. Family members felt let down by the services and were rather bitter about it. There psychosis susceptible member had more a patient role, of someone who is not responsible for his/her actions, which meant a big burden for the others. I did some qualitative research and what I found was that in families who had got an intervention there grew a balance of autonomy wishes of the psychosis susceptible person and the wish of families to protect. This may be an explanation of the outcome of (psycho-educational) family interventions; less hospitaliszations and les need for protecting environment. Fights about autonomy and protection precede often a psychosis which needs hospitalisation.

Evil

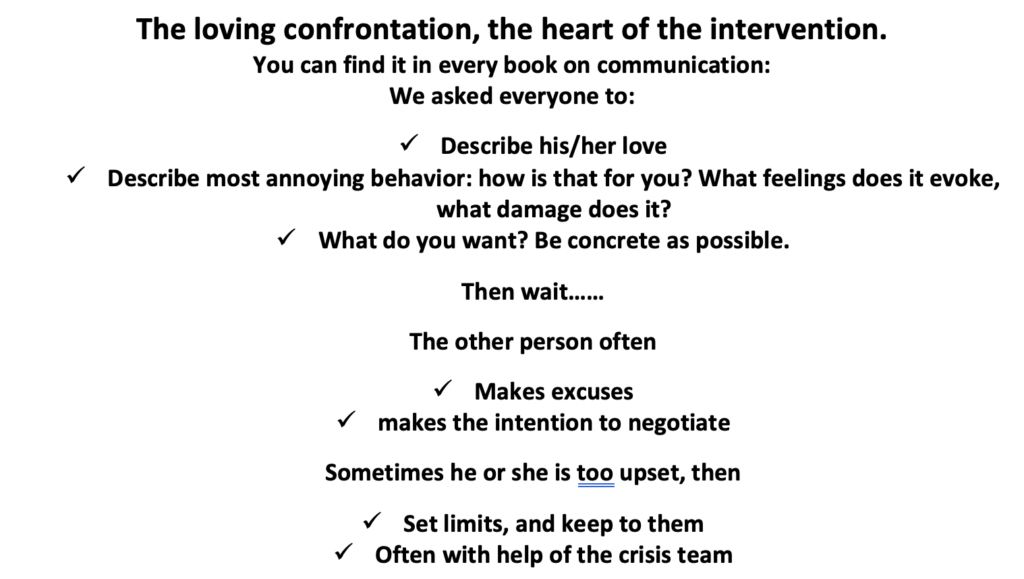

During my years working in the crisis center I was impressed by the effectiveness of this very simple intervention: just give feedback on the impact of behavior in a personal way. It worked not only with psychotic persons but also with persons considering suicide. Just ask families the question: how would it be for you to bury him? Families stopped discussing and burst in tears. We were not the only service doing this intervention also forensic clinics which hospitalised disturbed offenders did this too. And later this intervention is described by Haim Omer as nonviolent resistance or the new authority approach.

I studied cases published in the papers about bad things named above, that happened. Three things were prevalent. The offender had given many signs beforehand, known to services, worried families were ignored and there was a lot discontinuity of care. So that crucial information was lost and no one did really know the psychosis susceptible person.

Contemplation

We had one important alley, namely social instinct. Humans are fit to live in a group that is why they survived. Personal interaction seemed to awaken this instinct.

Social instinct is smothered when family and friends are replaced by institutional authorities, who try to cure and shape ’ the patient’. Bad behavior becomes a struggle for freedom. The same applies to follow up doctors advices. Medication for curing disappears in the toilet as soon as coercion is lessened. The psychosis susceptible person lands in the police station again and again. An clinicians say: ‘’This patient has no illness insight. So we must extend the coercion.’’

What we did instead was give continuity of care, organizing feedback again and again. When necessary we made a crisis plan with all involved. Most persons found a balance. And use some not too much medication. To help them to choose how to behave. Sometimes medication could be tapered to zero. And of course psychological therapies were given by team members after informed consent.

Psychosis, what is it?

We had the strong impression that it was a development crisis. Later I discovered with qualitative research that people who became psychotic had not had a decent adolescent period: having fights with authorities and making friends. There had not been enough opportunity to discover the world independent of their parent views. So the transition to adulthood went too fast,

A psychotic person can no longer rely on old thinking schemes of his own family or/and social group. In culture embedded commandments are often no longer there. He has to discover how the world really is, and the persons, he is related to, really are. But in order to do that he or she must meet them. When there is no one really present he must make a world of his own.

Challenging behavior can be seen a voyage of discovery. In order that someone does not get lost there must people around someone who give feedback and so form anchors in a confusing world.

A very unscientific contemplation II

I stated above that family relationships changed for the better after that family had set limits. In my career I had sometimes to set firm limits to dangerous behavior of persons who were in my care. Including even once a person losing his house (not my intention). Persons could be very angry with me. I later visited them taking responsibility for my actions in a conversation with them. Strangely but with them I had the best relationships. What was especially striking that they had more contact with their emotions. They could make very adequate observations and talk about it with feeling.

Maybe because they were no longer afraid that their emotions would hurt? That others but especially their social instinct would prevent them to harm?

Guilt

Maybe you don’t agree with me.? In your opinion a clinician is for therapy not for restoring social order? You think pressure and force is for other facilities. A clinician is for understanding. ?

In reaction to our disagreement I invite you to read about Lucas. Had his sister not entered the house than his mother would be dead now. The family is convinced that then he had completed his murderous act. His sister broke the relationship. But his parents had forgiven him, and his doctors had said, well he couldn’t help it, he had a psychosis! He even did not go to a judicial clinic, but to a ordinally psychiatric hospital for curing his schizophrenia. No one had talked about it ever since. Then in a family meeting I said Lucas we must talk about this. Lucas burst in tears. And they had the first talk in years. About the fright of the parents and about guilt that burdened Lucas for years and years.

Years later after my book was finished I visited his mother. Lucas had died, he had drunk himself to death. And his dad had died afterwards of sadness. Guilt is underestimated in damaging a person.

But it was not all bad. Lucas had spent his life walking in the park, picking up dogshit and put it in the letterbox of the owner of the dog. On an early morning he said to his neighbor: Look how beautiful the moon is, why do people stay in their houses, they ‘re mad! Lucas was popular in his village, when he was buried the church was full.

Psychosis susceptible persons must be treated as responsible persons. That is their human right. When they lose control over their behavior, other people and clinicians must prevent that harm is done. For a short time. Without unnecessary humiliation. Then together make plans to prevent accidents. Not only for the sake of the victims but also for preventing stigma and unbearable guilt.

Literature, a choice

Kuipers L., Leff J. & Lam D. (1992), Family Work for Schizophrenia: London: Gaskell

Lenior M.E. (2002), The social and symptomatic course of early-onset schizophrenia, five-year follow-up of a psychosocial intervention, Amsterdam: Thela Thesis

Nordentoft, M. e.a. (2006). (OPUS: a randomised multicenter trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first-episode psychosis–secondary publication). (Danish). Ugeskrift for Laeger,168, 381-384

Pater-Zijlstra, M.d.(2009), Omgaan met familieleden van patiënten van een act-team. In: Mulder, N. and Kroon, H.(red.), Assertive Community Treatment / druk 2, bemoeizorg voor patienten met complexe problemen (pp.307-326).Amsterdam: Boom Cure & Care

M.A. de Pater-Zijlstra (2012}. De eenzaamheid van de psychose, de rol van veilige strijd bij het ontstaan en het herstel van een psychose. Amsterdam: SWP

Omer H. (2011) The new authority: Family, school and community, Cambridge University Press

Robbins, I., (2009). Alone, the brain, sensory deprivation and isolation. BBC documentaire, http://topdocumentaryfilms.com/alone/.

Tarrier, N. e.a. (1994). The Salford Family Intervention Project: relapse rates of schizophrenia at five and eight years. British Journal of Psychiatry,165 (6), 829-832

Talma, H. (niet gepubliceerd), Transmurale gezinsbegeleiding bij chronische en acute psychosen, een evaluatie naar de huidige stand van zaken binnen het project transmurale gezinsbegeleiding

Zubek, J. P. (1969). Sensory Deprivation: Fifteen Years of Research. Appleton-Century-Crofts.